Almost five years ago now I was asked to appraise a movie script that told the story of the Polish pilots who had fought in the RAF during the Battle of Britain and beyond. I knew the vague outline of the story: the Polish flyers were overwhelmed by the better equipped Luftwaffe on home turf, escaped to France to continue the fight and, when France capitulated, made their way to England, where, despite their abilities, they were left to cool their heels. Only in the darkest hour of the Battle of Britain were they finally unleashed on the Germans, and proved themselves formidable opponents. In fact, 303 Squadron, the first of the “foreign” RAF units, became the highest scoring squadron in the Battle of Britain, although the British public, who in 1940 feted and idolised the Poles, and the government turned out to have very short memories once peace came.

The script told the story well enough, although I had one significant reservation. The squadron featured never existed and characters were amalgams of real people. Now that might have worked with a story like 633 Squadron, where everything apart from the Mosquitoes is fictitious, but this was a slice of history important to both the British and the Poles. My instinct was that there must be enough real stories around the actual 303 Squadron and the individuals in it to carry a movie. That’s when I discovered Jan Zumbach.

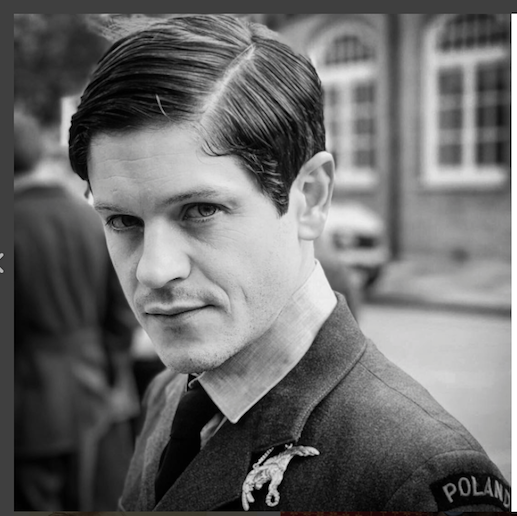

Of wealthy Swiss-Polish heritage, Zumbach’s life story was enough to fill several movies. The version of the script that eventually got made only tells the story of Zumbach – played in the new film Hurricane by Game of Thrones actor Iwan Rheon – when he and his fellow Poles were fighting in the skies over England. But there is so much more.

Born not far from Warsaw in 1915, Zumbach’s love for flying was ignited at the age of thirteen when the Polish Air Force put on an acrobatic display close to his sleepy hometown. His mother disapproved of his subsequent ambition to fly, so he enlisted in the army and then requested a transfer to the Air Force. At the age of 23 he was flying (antiquated) PZL fighters in the 111th Squadron and war was coming.

Infuriatingly for him, on the eve on the German invasion in September 1939, Zumbach broke a leg when his plane somersaulted during a night landing after clipping a truck parked across the runway. Hors de combat as Poland crumbled, he made his way to Romania and then to France, where he saw some action, before finally making his way to England, specifically a glum Blackpool.

There, weeks passed in a fug of boredom before, in July 1940, it was announced that a Polish squadron (albeit with British and Canadian commanding officers) was to be formed at RAF Northolt. There was more frustration, however, as the Poles had to endure English lessons and get used to RAF jargon (such as “Angels” for height) as well as conversion to thinking in miles per hour, feet and gallons, before they were allowed to fire a shot in their simmering anger at what was happening to their homeland.

Flying Hurricanes, rather than the more glamorous Spitfires, the Poles nevertheless proved to be tenacious fighters and were often considered positively reckless by their RAF counterparts. In No Greater Ally: The Untold Story of Poland’s Forces in WWII, author Kenneth K. Kosdan states: “Faced with spent ammunition or malfunctioning guns, Polish pilots [in the Battle of Britain] were known to ram enemy bombers, chew off wing tips or tails with their propellers, or maneuver their planes on top of the Germans and physically force them into the ground or English Channel.”

Zumbach himself was awarded eight kills and one probable between August 2 (when 303 became operational) and Oct 31, 1940 (the accepted end of the Battle of Britain). Like many of the Poles, who were often older and more mature than their RAF counterparts, he also found he scored highly with British women, as he revealed in his rather unreliable memoir On Wings of War (credited to “Jean Zumbach”).

“There was a thick notebook by the bed… it was X’s private diary, a detailed account, with critical commentary, of her love affairs. Even my limited English vocabulary was equal to this kind of subject matter, especially with the clues provided by the names of several members of my squadron. X had awarded them high marks, in contrast to her rather disparaging assessment of her fellow countrymen. By my rapid reckoning, her survey was based on a sample of approximately thirty. Sample thirty-one was delighted when she demonstrated how much her studies had taught here.”

Zumbach, later a Wing Commander, went on to lead 303 Squadron, but it was his post-war activities that set him apart. He, like other Poles who had served the Allies, had reasons to be disappointed in his treatment after VE Day. Thanks to the British government’s desire to appease Stalin, the Polish armed forces were not allowed to march in the Victory Parade in 1948 (some pilots were invited, but refused in solidarity with their banned comrades). And because he wouldn’t take part in any of the resettlement schemes for Poles, Zumbach claims in his memoirs that he was given three days to leave the country he had risked his life for. He reasserted his Swiss identity, gained a passport, and moved to Paris, his sense of justice tainted by the ungrateful attitude of the British authorities.

In the immediate post-war years an enterprising and amoral Zumbach used his newly-formed Flyaway charter company to smuggle diamonds, cigarettes, Swiss watches, gold and people (the latter to Israel) and even, in shades of The Third Man, penicillin (although at least the stuff he transported was genuine). By the late 1950s, however, he had gone more or less legit, running a restaurant and a nightclub in Paris and, as he put it, “getting fat”. Then, in 1962, war came calling again.

The offer was from President Moïse Tshombe of Katanga, which had ceded from the Congo, to put together the fledging country’s airforce, under the cover of an airline known as Air Katanga. It turned out to be a murky, messy and brutal conflict, with Zumbach’s rag-tag of an airforce providing ground support as Katanga battled Congolese and UN troops. Zumbach carried out more than sixty raids, but, outgunned by the UN, which eventually deployed SAAB jets, and out of pocket because of Tshombe’s bounced cheques, he returned to France, where he dealt in second-hand planes. But Africa wasn’t quite finished with him.

Iwan Rheon as Zumbach

It was another secessionist state that brought him back. In 1967 the Republic of Biafra broke away from Nigeria. War broke out between the Federal Government and the new state in July of that year. One of Biafra’s representative contacted Zumbach and asked if he could find them a bomber. He paid $25,000 for a mothballed Douglas B-26, which he sold on for $80,000 – only later did he find out the middleman charged Biafra £320,000. Zumbach was persuaded to deliver the plane in person and, eventually, to oversee it re-conversion to a bomber, complete with shark’s teeth on the nose like the famous Flying Tiger’s Kittyhawks.

Going by the name “John Brown”, he flew bombing missions for the new Biafran airforce (basically Zumbach and some trainees), destroying several aircraft and a helicopter on the ground, as well as killing a senior Nigerian army commander. This even though most of the “bombs” he used were improvised exploding cooking pots. The Sunday Times picked up the story:

“The first round in the soggy, bogged down civil war of Nigeria has gone to the secessionists of Biafra [thanks to] their judicious or lucky use of their one B-26 bomber.”

But again, Zumbach was on the wrong side and Biafra lost the war and tipped into a horrendous famine. He returned to France and wrote his memoirs and, rumour had it, his dealings in planes and sometimes weapons. His explanation for his colourful life? “Trouble comes naturally to some men, while soft living feels like a hair shirt.”

Jan Zumbach died in 3 January 1986, aged 70, in somewhat mysterious circumstances. The investigation into his death was closed by order of the French authorities without explanation. Maybe “trouble” had finally caught up with him. He was buried at Powązki Military Cemetery in Warsaw, Poland, a hero of 303 Squadron, home at last.

Hurricane, co-written by Robert Ryan and directed by BAFTA award winner David Blair, is released on September 7th. Some scenes in the film were shot at the splendidly atmospheric Battle of Britain Bunker (battleofbritainbunker.co.uk) in Uxbridge, which is open to visitors seven days a week and where a Hurricane in Polish RAF colours guards the entrance.

a good man to have on your side. I’m looking forward to see the film.