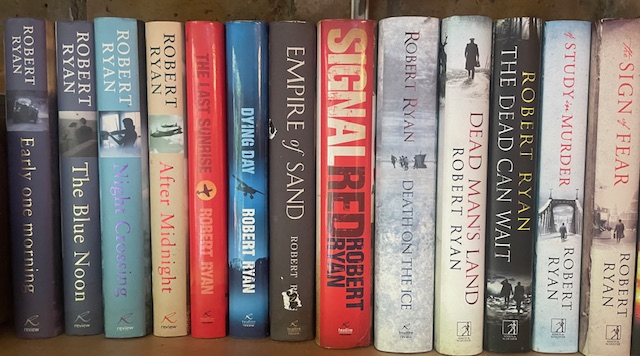

I fully intend to write about guitarist Nigel Price and his new album in my next column for the Camden New Journal, but I know I simply won’t have room to do him justice. Not only is Price our finest interpreter of the legacy of Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrell and (pre-pop) George Benson, he has been instrumental in maintaining the health of jazz in Britain.

(Above: Nigel Price. Photo by John McMurtrie)

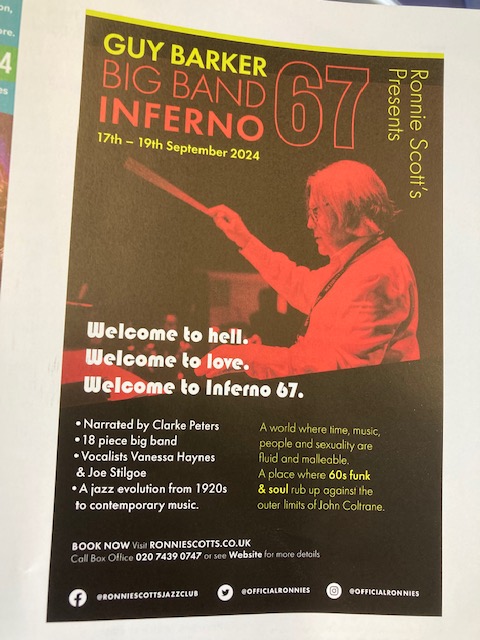

We in London tend to think that jazz revolves around Ronnie Scott’s, the Pizza Express, The 606, The Vortex, The Jazz Cafe and a handful of other venues. These might form the beating heart of British jazz, but the lungs, the organ that keep the music breathing, is found in the myriad of small clubs scattered around Britain. They act as incubators for new talent that will find its way to London eventually, but also offer a network where established players can always get a gig. Without the likes of Peggy’s Skylight in Nottingham, The Verdict in Brighton, Splash Point in Seaford and Eastbourne, the Bear Club in Luton, the Band on the Wall, Manchester, Jazz Jurassica, Lyme Regis, Palladino’s in Cardiff, the Blue Lamp, Aberdeen and many, many more, the life of a gigging jazz musician would be even more unsustainable than it is in the current climate, where rapacious Spotify has stripped out much of the traditional income stream.

These clubs are often run by enthusiasts and volunteers who wouldn’t recognise the word profit if it was on a Scrabble board before them (11 points by the way). Such is the precariousness of their existence that Covid threatened to kill some off as efficiently as it did those in care homes. It was why Price set up the Grassroots Jazz charity (https://www.grassrootsjazz.com), which fundraises and gives grants directly to venues. Recipients have included St Ives Jazz Club; Sound Cellar, Poole; Bebop Club, Bristol and Milestones, Lowestoft. Quite why he hasn’t been given some kind of government-sponsored gong for Services to Jazz is beyond me (although he and his group have won plenty of awards over the years).

His latest tour is with his Organ Trio to showcase the band’s new record It’s On! It is criss-crossing the country, calling at many of those self-same grassroots venues outside of London (although for those in the capital there’s an album launch at Pizza Express Soho on October 5th – https://www.pizzaexpresslive.com/whats-on/nigel-price-organ-trio). For the full list of gigs nationwide see https://nigethejazzer.com/.

It’s On by the Nigel Price Organ trio is a very good album indeed – he’s not just a fine guitarist but his fellow members (Ross Stanley on Hammond, Joel Barford on drums) are at the top of their game. The hefty touring schedule that the trio undertakes has given them real emotional, rhythmic and harmonic connection. In his sleeve notes the guitarist calls the collection of tunes on It’s On! a “mixed bag” but it’s a cohesive exploration of classic organ trio material, re-written, reworked and revamped by Price to give it a more modern feel, while not ignoring the voicings and killer swing that made guitar/organ/drums such a key feature of the jazz repertoire. Buy a physical copy if you can rather than streaming it. You can purchase It’s On! and his other records on vinyl and CD at Price’s website above. And then catch the trio live and help keep jazz in Britain breathing.